Ray Pospisil’s Voice and His SilenceThe Language of Inevitability  A rather ordinary voice in many respects, even-toned and tempered, modest in volume, its colors quite varied, but muted—. More a matter of inflection than expression, its most pronounced dramatic quality was not emotion, but momentum. You might not notice it at first in that crowd of those compelled to speak aloud. But once it caught your ear, it became difficult to stop listening until the voice itself chose silence. And even then, at the end of a poem—one’s ear lingered. And even now, at the end of all the poems—one’s ear returns, in anticipation of hearing it again. Some sounds “work their way into our bones and nerves/with every bell vibration shaking over us.” Subtle, yet persistent. The voice of Ray Pospisil was a sound like that. A rather ordinary voice in many respects, even-toned and tempered, modest in volume, its colors quite varied, but muted—. More a matter of inflection than expression, its most pronounced dramatic quality was not emotion, but momentum. You might not notice it at first in that crowd of those compelled to speak aloud. But once it caught your ear, it became difficult to stop listening until the voice itself chose silence. And even then, at the end of a poem—one’s ear lingered. And even now, at the end of all the poems—one’s ear returns, in anticipation of hearing it again. Some sounds “work their way into our bones and nerves/with every bell vibration shaking over us.” Subtle, yet persistent. The voice of Ray Pospisil was a sound like that.

I have spent a good deal of my life on islands. I was born on one, I grew up on one, and I have traveled to many others alone. The proximity of an ocean, the sound of its waves beating constantly against a shore, can be drowned out for a time when the ear is distracted or shifts focus. But late at night, when less perpetual clamors fade, before the return of that hour “when digits fall and radio clicks/on perky chat” —the sound of the surf will often resurface in the depths of the ear with startling intimacy. That’s Ray’s voice again, calm and inescapable.

Talk is cheap, and we all have lots to say—we all have an opinion or two or three on absolutely everything. Ray himself had strong opinions and he expressed them well, with a quietly humorous savagery. But it is not that aspect of voice I am talking about here. Subjectivity adds weight, psychological or political or otherwise. But it is form, the objective form of a voice, its tactile music, which adds breadth. The opinions we voice create us as individuals, they delineate our identities, they separate us and then, at times, reunite us. But the sound of the voice, its music, is a force that expands rather than contracts—that leads, not to the one, but to the all. And that communal music underlies language in a way which might seem entirely inexplicable were it not for this science that Ray studied called poetry.

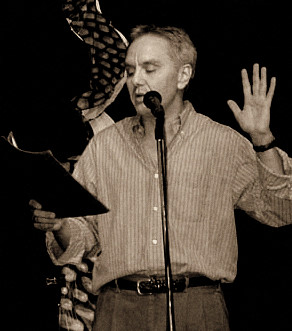

Last February, a handful of Ray Pospisil’s colleagues returned to the unassuming laboratory where many of his most resonant poetic experiments were first unveiled: a neighborhood bar on the corner of 13th Street and 2nd Avenue in Manhattan’s East Village where, for several years running, a rag-tag band of poets were in the habit of gathering on Monday nights to share what they had been writing or revising the week before. It was an impromptu memorial, called to mark the third anniversary of Ray’s death—so hastily announced that there was little time to muster the sort of socially sentimental hyperbole that often clutters such occasions. I must confess that I was a little off my game that evening. Not really in the mood to take to the open mike, I fumbled through a poem of Ray’s that I was barely familiar with.

Paint peels

enamel thins

components deteriorate

faucets wear.

The sentiments of this Drip in free-verse seemed a convenient shorthand for my state of mind that evening. Yet relieved of my own active desire to perform, I was primed for more passive revelations. I was freed to listen, to simply listen. One by one, a handful of poets—those available on such short notice, individuals of an almost alarming diversity—took the stage to recite a poem or two of Ray’s that had particularly moved them. Some had been on more intimate terms with Ray than others, some more-so or less-so in tune with his poetic praxis—and yet each and every one read his words with such clarity that I found myself astonished at the vibrancy of these written documents that Ray had left behind, at the level of sheer communication they were able to sustain so effortlessly. More than anything else, I quickly realized, it was the music of the language which inspirited these readers—a music so carefully calibrated as to be common to all, to each of the many different voices that became instrumental to it that night. This, I assured myself as I listened more and more closely, was not a music imposed on language by thought, but a music discovered in language, its innate music. Readers with no notion whatsoever of metrical scansion sailed through these poems without missing a beat. Every poem seemed to rock unconsciously to the rhythm with which it was composed, and to surrender itself to the entire spectrum of readers without losing its own integrity. This was a voice not dependent on the one, but on the all. Not heroic then, Ray’s voice, but rather inevitable.

It is above all at the sea level of blank verse where Ray found his métier, where he discovered his universally communicable sense of rhythm. Of all the verse forms, blank verse demands most from the poet in the way of self-abnegation. At its best it can render a poet invisible. Successful blank verse fails when it calls attention to itself the way other formalist contrivances can—and even must, if they are to hold our collective interest. The demand for novelty in rhyme and repetend, for conscious dissembling of the sestina’s obsessive identity, for the unexpected ‘nut in the oatmeal’ of metrical substitution, for the premature volta or the climactic alexandrine—such self-conscious costumes seem out of place in the workaday wardrobe of blank verse. On the contrary, this drabbest member of the verse family seems more concerned with accepting language as it is given, than with decorating it to suit one’s tastes or whims. Rather than addition, it seems to thrive on subtraction—on a negative sculpting which removes in order to discover, a stripping away of armor and ornament in order to reveal the fundament of form. Once found, that form is undeniable. It is the familiar voice of the language itself, etched in supple stone.

Perilous, I suspect, for a non-native speaker to master any given language’s blank verse. And I concede that there may be, as well, more than one blank verse per language: there may be an urban blank verse, a rural blank verse, there may even be a dozen regional and temporal blank verses poised to assail my faith in fundamentals, in universals. Indeed, I have heard earnest discussions of the form too easily degenerate into contentious battles over personal dialect and identity—yet such passionate nationalisms, as their scale shrinks, seem directly proportionate to the failures of their attempted blank verses. It can often be those unique aspects of language most dear to one’s self that must be sacrificed in order to begin blank verse’s approach to the elemental. “They get so animated, no one hears/that humming in the background. Could it be?” Accustomed to the stellar notes of the cultural aria, the hum of the primordial chorus takes some getting used to.

Ray was several times quite explicit to me about his preference for the field as a unit, as opposed to the line. I have always strived, when reading aloud, to make it relatively clear to a listener just where my lines of verse begin and end, despite numerous enjambments. Early on I noticed how unconcerned Ray seemed with such aural delineation. His vocal line was, instead, continuous— more contingent on breath than on pattern or page. Rather than end-stopping his verses in recitation, he preferred to let them propel themselves, via their own natural momentum, into fields of sense—a tendency which I am convinced contributed immeasurably to his ability to communicate so freely with an audience, almost any audience.

Rhyme is, of course, a highly effective tool for impressing upon the ear a poem’s linear architecture—so palpable is it, that the ear can almost see it. Such willful music yields its own intoxicatingly clear moments. Blank verse, on the other hand, tends to blur the edges of those moments—all the while flirting with but still skirting the boundaries of that other quantifiable unit, the sentence. In blank verse it is often the more relaxed rhythm of conversation that predominates; its caesurae are more comfortably spacious. Often when Ray read his blank verse aloud, you felt that he was just talking to you, just chatting away in your ear. Even his anger (and he had a fair number of righteously angry poems) had an affably conversational tone. And yet, almost unnoticed, it was that rigorously self-effacing meter he’d discovered within the words themselves that made them sneak up on you, and stay with you, in a way that ordinary ephemeral conversation and even emphatic rant never could. Blank verse made of Ray a casual mesmerist. The poems themselves remain as unostentatious as they are indelible. Never has that been more evident to me than on that night last February when I saw how the potency of the language had been so carefully excavated from the metrical tissue of the text itself, that it was still accessible to the common voice even though the particular voice had long since fallen silent. There seemed to be no other way to read these poems. I remember saying to myself, “These poems are already beginning to last.”

Sometimes a poet finds the right voice, his or her own. Contrariwise, sometimes it is a delight to watch a poet struggle with a voice that is not their own—the resultant frictions and fireworks can be something to behold! As one reared on the avant-garde, I am rarely averse to innovation for innovation’s sake, and each of us no doubt has some special quirk all our own with which we may fruitfully pioneer a pyre of paper. But it was very much in keeping with Ray’s temperament that he did not seek innovation as avidly as he sought that common ground of speech which unites and embraces, rather than isolates and distinguishes. As a result it is easy to overlook his blank verse accomplishments. Yet even those poems in which he mastered a more conspicuous art of fragmentation—candidates for the so-called masterpiece, poems like the justly praised Insomnia— could never shatter us with such abysmal certainty were they not anchored by those more involuntary rhythms they were so intent on disturbing.

Alas, the fracturing, the disintegration, seem in retrospect almost as inevitable as the rhythmic trajectory of the language. All this talk of the common ground, the primal embrace, the elemental depths of language is not, ultimately, to be confused with some dewy-eyed state of touchy-feely interconnectedness. That wasn’t it at all. Ray was warm, definitely, but quite reserved—and his very private daemons were deadly. It was another night on 13th Street and 2nd Avenue, years earlier—a night in 2007, when Ray Pospisil approached the mike, mumbled a few lines with an uncharacteristic tentativeness, began again, stumbled again, and then fell strangely mute. A muttered apology soon followed, and a stunned audience watched in a sort of confused dread as Ray, one of the few truly reliable readers around, returned, head bowed, to his stool at the bar, unable to read on for reasons few could fathom and which he chose not to share.

I have limited the scope of these remarks to the music of his verse, to its form—but any study of the content of these verses, especially toward what for many was the unexpected end of Ray Pospisil’s outwardly undemonstrative life, will reveal that the underlying rhythms which he was so adept at surrendering to were often dark and chthonic ones whose seductions proved ultimately as irresistible as the inexorability of his blank verse.

I’ll swim until I cannot see the shore

and wade there, feeling all the fish below

me, nibbling at my dangling toes. I’ll turn

and watch the sun descend below the dim

horizon line and wallow in the dark

until I weaken down to ecstasy

of being so absorbed and spread throughout

the vast expanse, among the shells and bones

and dust.

In the opening salvo of his poem, “Grace Note,” Ray comes right out and asks point blank, “I wonder if I’ll die tonight?” Yet in verse after verse in his last years that same question recurs over and over again—in myriad disguises, but always unflinchingly—as if his intimacy with one depth, that of language, had initiated him into other depths as well. For any veteran mariner of the unconscious, that’s not as fanciful a statement as it seems.

and dust. And when I’m all dissolved by salt

and current, scattered in the swirling mix,

I’ll vibrate to the calling song of whales

from pole to pole and flow from ocean to

the next on plates of shifting geologic

time and feel the pull of looming moon.

That poem, “Dissolving,” from Ray’s posthumously published collection, The Bell, was originally called “Change” in an earlier unpublished manuscript entitled Ghost House. Though his death may have shocked some, for others—all things being connected—the silence of the singer is already prefigured in his song.

Poseidon Elegy

for Ray Pospisil

I suddenly recalled the pounding surf last night

— As I lay in my bed attempting sleep.

I suddenly recalled how years before I lay

— And listened to its violent lullaby—

Its measured pulse resounding in that distance which

— The darkness of my room invited in.

Perhaps too many buildings block the soundlines now;

— Too many motorbikes congest the air,

Their eager little engines drowning out true power

— With counterfeit bravado all night long.

Indeed the barking dogs seem to have multiplied

— Proportionate to that which so disturbs them:

The reeling of those drunk machines whose opaque shadows

— Obscure the moon at which they might have howled.

I tossed a bit—turned—tossed some more—and then lay still

— And slipped into sleep’s thoughtlessness until

The hour before dawn—when I arose and heard

— (Before the din of thoughtfulness returned,

Before the morning’s earliest motors coughed and spit,

— Before its earliest birds began to sing)

The hollow boom and long low roar of distant surf,

— The sound of which at first was startling.

Could it be true that I have not been listening—

— Distracted by the clamor of a world

Whose exponential tedium and tumult numb

— And paralyze my poor defenseless ear?

Or is it that some distant storm approaching land

— So strengthens the brute force of wind and wave

That neither media-drench nor traffic-drone can muzzle

— That myth of might this Triton’s blows recall?

In any case, surrender’s now my only thought—

— Surrender to this monster of delight—

This beating beating ’gainst the drum within my ear;

— This shaking of the ground beneath my feet;

This fundamental trembling that forever binds

— All things above to all that heaves beneath.

Such untamed power fills me with profound relief.

— I hold my heart. I neither breathe nor think.

Its breakers breaking at earth’s edge and at world’s end—

— Eternally external is this thunder

Which crumbles and consumes, which grinds down bit by bit

— To fine and then to finer grains of sand

All that we’ve built, and all that we have built upon;

— All swept away, devoured and dissolved.

With a continual apocalypse like this

— What need have we for terrorist incursions?

We need but passive strength and patience to endure

— The squalid foibles of the minor makers,

The vulgar demiurge’s deafening commotions,

— His ziggurats and idle tabernacles,

His automated tumuli, those monuments

— His robots raise so rudely up amongst us.

We need but true Titanic patience to endure

— Until such time as the most ancient sea

Erases all we think we are—as it restores

— The lovely rhythm of the endless void.

|